JOHN LENNON: ESSENCE AND REALITY PART Part 6: “Happy Xmas (War Is Over)”

6: “Happy Xmas (War Is Over)”

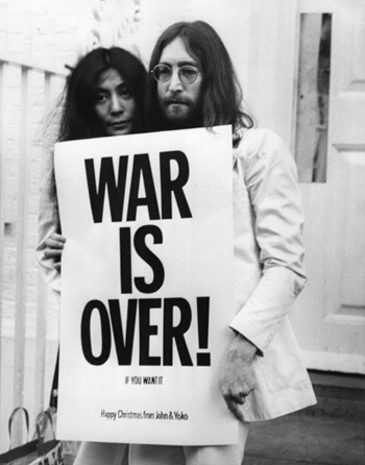

“A very merry Christmas, and a happy New Year. Let’s hope it’s a good one, without any fear.” So sang John and Yoko on their December 1971 single, “Happy Xmas (War Is Over)”. They were then running, as the main aspect of their self-conscious lives as “artists in the public eye”, a campaign for peace. War, they said, is over – if you want it. In other words, if all of us desire peace, we will have it. We just put our weapons down. This was the time of the Vietnam War, when expressing such sentiments was something of an act of defiance against “the establishment”, and we now know just with what serious concern the Nixon government viewed John and Yoko’s activities. Lennon’s Christmas song used the occasion to protest against the Vietnam war, to oppose any and all wars, and to call us to think about our personal responsibility for the state of the world. Could it be true that if I really wanted war to be over, I could do something to achieve that? Could it be that if enough of us, all over the world, wanted peace, we could bring that about?

World peace, is in some respects, a dream. But what if enough people defy the accepted wisdom and dream the same dream? The deeper significance of “Happy Xmas (War Is Over)” is that John and Yoko very shrewdly used the assured interest in the season, and the music and radio industries’ need for new Christmas records, to broadcast their pro-peace anti-establishment message to an audience which might otherwise never have heard it. For that to succeed it had to sound like a Christmas song: and it does. It is something of an anthem for peace, but it is also simultaneously and sincerely a seasonal expression of good wishes.

The single achieves a great aural impact. It opens with whispers: Yoko first with “Happy Christmas, Kyoko”, and then John with “Happy Christmas, Julian”, addressing their children by their previous marriages. Quickly, it soars into what are arguably excessive lashings of elaborately arranged sound, until it closes with explosive cries of “Merry Christmas, everybody”. Phil Spector produced it in his idiomatic style: at times it sounds as if the massed choir is right in your middle ear, singing the chorus “War is over, if you want it”. The last part of the song features a splendid counterpoint: Lennon sings the verses against the vast backdrop of that refrain, sounding crystal clear. The choir, incidentally, was the Harlem Community choir from New York, and they packed a punch. Sometimes, I think, too much of a punch. The chief reason I can only rarely hear this single without losing my appreciation of it is its over-the-top Phil-ification, and not Yoko Ono’s voice, which I know some people cannot accept.

But it is not enough just to wish for a merry Christmas. There is something here which goes beyond anything which Lennon ever explored. Lennon used Christmas for his own purposes, and that in itself is hardly wrong. However, if instead of using Christmas, we learn from it, the situation is different.

If we enter deeply into the spirit of Christmas, we will at some point embrace suffering; we will accept to close our lips on thorns, because we have to evaluate ourselves in the light of the most exacting demands possible. “Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you” taught Jesus. None of us do, few of us try even once in our lives. The feast is glorious only because it celebrates the coming of Jesus the Messiah. To enter the spirit of the feast is to consciously struggle to live up to his teaching.

I have read interpretations of the season by philosophers, theologians, atheists, agnostics, New Age gurus, and journalists. I have seen many festive films and programs. They strive to make an impact, but most of them strike me as more or less sentimental. As I recall, only the efforts of Annie-Lou Staveley and G.K. Chesterton ever touched me deeply and lastingly. In my opinion, the great multitude fail because they lack sufficient sense of reality: they romanticize, present easy platitudes, and conjure cozy visions of a baby in swaddling clothes. But the birth of that baby only has any significance because he was, as the Orthodox say, the theanthropos, the God-Man, and because of what he did and taught as an adult.

So what is it about loving our enemies and praying for those who persecute us which makes it so difficult for us to make an honest effort to do so? It is urged far more than often that it is implemented. It is preached far more often than it is even meditated upon. As George Adie would say, let’s not waste time saying that it’s difficult, because it is, in fact, very nearly impossible. It does not mean loving or praying for those whom we merely dislike. It does not even mean fair being to those who are unfair to us. It requires freeing ourselves, if only briefly, from the negative emotions to which we are so attached (I might say addicted), and rousing something almost divine in ourselves for the sake of an enemy, which is not just someone who doesn’t like us, but someone who is actively trying to harm us. Most of us have or have had enemies of some degree: bullies at school, people who exploit or thieve from us, people who run campaigns against us at our work, and some few of us have enemies who want to trash our reputation, financially ruin us, or even physically harm or kill us. And then, once we admit to the deeply troubling fact that we may in fact have an enemy, we come to the massive question: can we love them? Whatever “love” may be, it is immense. A feeling of love cannot be a small or a slight emotion. It must be something which humbles us when we feel it.

My point is that unless we start to approach this question, we are not seriously approaching Christmas in anything like its full significance, and that means we are missing the potential experience and even illumination which it offers us. John Lennon’s season was a Xmas, a feast where the Christ is a cultural memory, a syllable in a secular word. Yet, better than many soi-disant Christians, Lennon understood that there is a question for us: “And so this is Christmas, and what have we done? Another year over, a new one just begun.” Lennon then went on to express the usual sort of Chrissy cheer “I hope you have fun, the near and the dear ones, the old and the young.” But he also had a more poignant message: “And so this is Christmas, for weak and for strong, for rich and for poor ones, the world is so wrong.”

Lennon had wanted, he said, to write a Christmas standard, and it as it happens, he seems to have succeeded. It was a top ten hit in 1971 and, I think in 1972 in England. In 1980, after his death, it was number 1 in England, and has been covered many times. The song is still played each year, and may even be more widely known now than it was in Lennon’s lifetime. While I find the melody of the verses is particularly apt, for me, the song approaches greatness but somehow falls short. I think that if it is becoming a standard, it is more because of the comparative mediocrity of other Christmas songs. I am not speaking of Christmas carols here: they exist within a definitely Christian context, so their relation to the exigencies of the Christian teaching is always apparent. They express the wonder and joy of Christmas, but they point to Jesus, and hence indirectly to his teaching. Even then, there are those like the Coventry Carol which fully express the antipathy of the world, with its raging Herods seeking to destroy the hope.

But that is a carol. How can one sing about Christmas to a secular world, from a secular standpoint? To my taste, many have tried, but failed, because the associations of Christmas with peace and hope are too strong. Unless these positive qualities are given their due weight, which is quite difficult in a secular approach, the result is liable to be cynical. Everyone who sings about Christmas has to consider how to address its intrinsic nature as a Christian festival. Some writers ignore this, which is never convincing, as it only trivializes what we still instinctively sense is a tremendous religious celebration of spiritual light. Others, like Jethro Tull, bemoan the cheapening of Christmas, but end up sounding unbearably preachy.

When he was with Emerson, Lake and Palmer, Greg Lake came close, perhaps, to some balance in “I Believe in Father Christmas”. Lake has a powerful voice, and he produced some magnificent melodies. The song is marked by trenchant attacks on hypocrisy, and its punch line “the Christmas you get, you deserve”. It also features some magical lines: “And I believe in Father Christmas, I look to the sky with excited eyes … that Christmas-tree smell, and eyes full of tinsel and fire.” But overall, its tenor becomes just a little too self-important, too much of a finger-pointing exercise, to succeed as a Christmas song. Unless the secular critique acknowledges the sublimity of Christmas, and includes the singer in its critique, it is perhaps likely to fail.

The fact is that we still feel something innocent, peaceful, silent and charitable in ourselves at Christmas. A friend of mine once said of St John’s Gospel that when you read it, you feel as a reality that love can never be defeated, that it will rule the universe, and that in some mysterious way, it always has. I think that something similar is true of Christmas, but Christmas is not a story you have to read. The wise ones in the church of the fourth century, who used the astonishingly powerful writing of Matthew and Luke to create Christmas, wrote a book which rewrites itself each year in deeds and in thought.

Lennon’s song duly acknowledges the celebration and also the critical ideas and moods that Christmas arouses today. It is much subtler than Lake’s piece. To start with, Lennon includes himself in his critique. He asks “what have we done”? He wishes his audience well, and he includes everyone in his sentiments: old and young, weak and strong, the poor and the rich. Note that the wealthy and powerful are not excluded. To my mind, Dylan’s “Masters of War” blunts its own point by wishing the speedy death of the corporate criminals he rightly excoriates. No, Lennon makes his point not by excluding anyone but by stressing that the disadvantaged must be included, and putting some unobtrusive but noticeable feeling into the line: “the world is so wrong”. According to Jesus’ teaching, we must love even the masters of war.

On my reading, then, the greatness of “Happy Xmas (War Is Over)” is that it is true to the spirit of Christmas, an even more remarkable achievement because it is not written from inside Christianity. It presents both the positive aspects of Christmas and the challenge. True, Lennon’s invitation to peace is not so powerful as Jesus’ instruction to love one’s enemies and pray for those who persecute us, but it is in that direction. The over-kill in Lennon’s presentation is in the sound, not the song as written. And Lennon’s question still remains: what have we done for peace? Surely, in some small way, in some situation close to us, we can at least attempt something to bring some people together, to leave some little more understanding than there had been.

Which brings me to my last point, one I shall return to with Lennon. In a way, Lennon’s protest is not against Christianity but the failure of Christians to live up to Christianity. As with so many other critics, he is, on a deeper analysis, not against Christianity but against a lack of it, meaning here by “Christianity” the putting into practice of its teachings.

This leaves us with some interesting perspectives, and of course, it suggests an approach which might fruitfully use to explore the Lennon classic “Imagine”. But before we do, there are some songs from Lennon’s Beatles years which will help us see better how Lennon made the journey to “Imagine”. So in the next Lennon blog we will consider “There’s A Place” from the Beatles’ first album, Please Please Me, and “Girl” from Rubber Soul.

Joseph.Azize@googlemail.com

Joseph Azize has published in ancient history, law and Gurdjieff studies. His first book “The Phoenician Solar Theology” treated ancient Phoenician religion as possessing a spiritual depth comparative with Neoplatonism, to which it contributed through Iamblichos. The third book, “George Mountford Adie” represents his attempt to present his teacher (a direct pupil of Gurdjieff and Ouspensky) to an international audience.

“A very merry Christmas, and a happy New Year. Let’s hope it’s a good one, without any fear.” So sang John and Yoko on their December 1971 single, “Happy Xmas (War Is Over)”. They were then running, as the main aspect of their self-conscious lives as “artists in the public eye”, a campaign for peace. War, they said, is over – if you want it. In other words, if all of us desire peace, we will have it. We just put our weapons down. This was the time of the Vietnam War, when expressing such sentiments was something of an act of defiance against “the establishment”, and we now know just with what serious concern the Nixon government viewed John and Yoko’s activities. Lennon’s Christmas song used the occasion to protest against the Vietnam war, to oppose any and all wars, and to call us to think about our personal responsibility for the state of the world. Could it be true that if I really wanted war to be over, I could do something to achieve that? Could it be that if enough of us, all over the world, wanted peace, we could bring that about?

World peace, is in some respects, a dream. But what if enough people defy the accepted wisdom and dream the same dream? The deeper significance of “Happy Xmas (War Is Over)” is that John and Yoko very shrewdly used the assured interest in the season, and the music and radio industries’ need for new Christmas records, to broadcast their pro-peace anti-establishment message to an audience which might otherwise never have heard it. For that to succeed it had to sound like a Christmas song: and it does. It is something of an anthem for peace, but it is also simultaneously and sincerely a seasonal expression of good wishes.

The single achieves a great aural impact. It opens with whispers: Yoko first with “Happy Christmas, Kyoko”, and then John with “Happy Christmas, Julian”, addressing their children by their previous marriages. Quickly, it soars into what are arguably excessive lashings of elaborately arranged sound, until it closes with explosive cries of “Merry Christmas, everybody”. Phil Spector produced it in his idiomatic style: at times it sounds as if the massed choir is right in your middle ear, singing the chorus “War is over, if you want it”. The last part of the song features a splendid counterpoint: Lennon sings the verses against the vast backdrop of that refrain, sounding crystal clear. The choir, incidentally, was the Harlem Community choir from New York, and they packed a punch. Sometimes, I think, too much of a punch. The chief reason I can only rarely hear this single without losing my appreciation of it is its over-the-top Phil-ification, and not Yoko Ono’s voice, which I know some people cannot accept.

But it is not enough just to wish for a merry Christmas. There is something here which goes beyond anything which Lennon ever explored. Lennon used Christmas for his own purposes, and that in itself is hardly wrong. However, if instead of using Christmas, we learn from it, the situation is different.

If we enter deeply into the spirit of Christmas, we will at some point embrace suffering; we will accept to close our lips on thorns, because we have to evaluate ourselves in the light of the most exacting demands possible. “Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you” taught Jesus. None of us do, few of us try even once in our lives. The feast is glorious only because it celebrates the coming of Jesus the Messiah. To enter the spirit of the feast is to consciously struggle to live up to his teaching.

I have read interpretations of the season by philosophers, theologians, atheists, agnostics, New Age gurus, and journalists. I have seen many festive films and programs. They strive to make an impact, but most of them strike me as more or less sentimental. As I recall, only the efforts of Annie-Lou Staveley and G.K. Chesterton ever touched me deeply and lastingly. In my opinion, the great multitude fail because they lack sufficient sense of reality: they romanticize, present easy platitudes, and conjure cozy visions of a baby in swaddling clothes. But the birth of that baby only has any significance because he was, as the Orthodox say, the theanthropos, the God-Man, and because of what he did and taught as an adult.

So what is it about loving our enemies and praying for those who persecute us which makes it so difficult for us to make an honest effort to do so? It is urged far more than often that it is implemented. It is preached far more often than it is even meditated upon. As George Adie would say, let’s not waste time saying that it’s difficult, because it is, in fact, very nearly impossible. It does not mean loving or praying for those whom we merely dislike. It does not even mean fair being to those who are unfair to us. It requires freeing ourselves, if only briefly, from the negative emotions to which we are so attached (I might say addicted), and rousing something almost divine in ourselves for the sake of an enemy, which is not just someone who doesn’t like us, but someone who is actively trying to harm us. Most of us have or have had enemies of some degree: bullies at school, people who exploit or thieve from us, people who run campaigns against us at our work, and some few of us have enemies who want to trash our reputation, financially ruin us, or even physically harm or kill us. And then, once we admit to the deeply troubling fact that we may in fact have an enemy, we come to the massive question: can we love them? Whatever “love” may be, it is immense. A feeling of love cannot be a small or a slight emotion. It must be something which humbles us when we feel it.

My point is that unless we start to approach this question, we are not seriously approaching Christmas in anything like its full significance, and that means we are missing the potential experience and even illumination which it offers us. John Lennon’s season was a Xmas, a feast where the Christ is a cultural memory, a syllable in a secular word. Yet, better than many soi-disant Christians, Lennon understood that there is a question for us: “And so this is Christmas, and what have we done? Another year over, a new one just begun.” Lennon then went on to express the usual sort of Chrissy cheer “I hope you have fun, the near and the dear ones, the old and the young.” But he also had a more poignant message: “And so this is Christmas, for weak and for strong, for rich and for poor ones, the world is so wrong.”

Lennon had wanted, he said, to write a Christmas standard, and it as it happens, he seems to have succeeded. It was a top ten hit in 1971 and, I think in 1972 in England. In 1980, after his death, it was number 1 in England, and has been covered many times. The song is still played each year, and may even be more widely known now than it was in Lennon’s lifetime. While I find the melody of the verses is particularly apt, for me, the song approaches greatness but somehow falls short. I think that if it is becoming a standard, it is more because of the comparative mediocrity of other Christmas songs. I am not speaking of Christmas carols here: they exist within a definitely Christian context, so their relation to the exigencies of the Christian teaching is always apparent. They express the wonder and joy of Christmas, but they point to Jesus, and hence indirectly to his teaching. Even then, there are those like the Coventry Carol which fully express the antipathy of the world, with its raging Herods seeking to destroy the hope.

But that is a carol. How can one sing about Christmas to a secular world, from a secular standpoint? To my taste, many have tried, but failed, because the associations of Christmas with peace and hope are too strong. Unless these positive qualities are given their due weight, which is quite difficult in a secular approach, the result is liable to be cynical. Everyone who sings about Christmas has to consider how to address its intrinsic nature as a Christian festival. Some writers ignore this, which is never convincing, as it only trivializes what we still instinctively sense is a tremendous religious celebration of spiritual light. Others, like Jethro Tull, bemoan the cheapening of Christmas, but end up sounding unbearably preachy.

When he was with Emerson, Lake and Palmer, Greg Lake came close, perhaps, to some balance in “I Believe in Father Christmas”. Lake has a powerful voice, and he produced some magnificent melodies. The song is marked by trenchant attacks on hypocrisy, and its punch line “the Christmas you get, you deserve”. It also features some magical lines: “And I believe in Father Christmas, I look to the sky with excited eyes … that Christmas-tree smell, and eyes full of tinsel and fire.” But overall, its tenor becomes just a little too self-important, too much of a finger-pointing exercise, to succeed as a Christmas song. Unless the secular critique acknowledges the sublimity of Christmas, and includes the singer in its critique, it is perhaps likely to fail.

The fact is that we still feel something innocent, peaceful, silent and charitable in ourselves at Christmas. A friend of mine once said of St John’s Gospel that when you read it, you feel as a reality that love can never be defeated, that it will rule the universe, and that in some mysterious way, it always has. I think that something similar is true of Christmas, but Christmas is not a story you have to read. The wise ones in the church of the fourth century, who used the astonishingly powerful writing of Matthew and Luke to create Christmas, wrote a book which rewrites itself each year in deeds and in thought.

Lennon’s song duly acknowledges the celebration and also the critical ideas and moods that Christmas arouses today. It is much subtler than Lake’s piece. To start with, Lennon includes himself in his critique. He asks “what have we done”? He wishes his audience well, and he includes everyone in his sentiments: old and young, weak and strong, the poor and the rich. Note that the wealthy and powerful are not excluded. To my mind, Dylan’s “Masters of War” blunts its own point by wishing the speedy death of the corporate criminals he rightly excoriates. No, Lennon makes his point not by excluding anyone but by stressing that the disadvantaged must be included, and putting some unobtrusive but noticeable feeling into the line: “the world is so wrong”. According to Jesus’ teaching, we must love even the masters of war.

On my reading, then, the greatness of “Happy Xmas (War Is Over)” is that it is true to the spirit of Christmas, an even more remarkable achievement because it is not written from inside Christianity. It presents both the positive aspects of Christmas and the challenge. True, Lennon’s invitation to peace is not so powerful as Jesus’ instruction to love one’s enemies and pray for those who persecute us, but it is in that direction. The over-kill in Lennon’s presentation is in the sound, not the song as written. And Lennon’s question still remains: what have we done for peace? Surely, in some small way, in some situation close to us, we can at least attempt something to bring some people together, to leave some little more understanding than there had been.

Which brings me to my last point, one I shall return to with Lennon. In a way, Lennon’s protest is not against Christianity but the failure of Christians to live up to Christianity. As with so many other critics, he is, on a deeper analysis, not against Christianity but against a lack of it, meaning here by “Christianity” the putting into practice of its teachings.

This leaves us with some interesting perspectives, and of course, it suggests an approach which might fruitfully use to explore the Lennon classic “Imagine”. But before we do, there are some songs from Lennon’s Beatles years which will help us see better how Lennon made the journey to “Imagine”. So in the next Lennon blog we will consider “There’s A Place” from the Beatles’ first album, Please Please Me, and “Girl” from Rubber Soul.

Joseph.Azize@googlemail.com

Joseph Azize has published in ancient history, law and Gurdjieff studies. His first book “The Phoenician Solar Theology” treated ancient Phoenician religion as possessing a spiritual depth comparative with Neoplatonism, to which it contributed through Iamblichos. The third book, “George Mountford Adie” represents his attempt to present his teacher (a direct pupil of Gurdjieff and Ouspensky) to an international audience.

Comments

Post a Comment